|

This story is a chapter of the book The Airship Experience and appears courtesy of R. G. Van Treuren |

BLACKDOG: A GOOD SHIPMATE |

||

By C. E. Aldrich |

||

It all started back in 1944 when a small, ugly dog decided to join the Navy. At Fisher’s Island, New York, was stationed a small detachment of Navy “G” type airships. Since sailors are often inclined to adopt stray dogs, ugly or not, this homeless mutt was taken into the outfit as mascot. The men never did get around to giving him a name, referring to him simply as “Black Dog” [usually pronounced and written as one word: “Blackdog.”] |

||

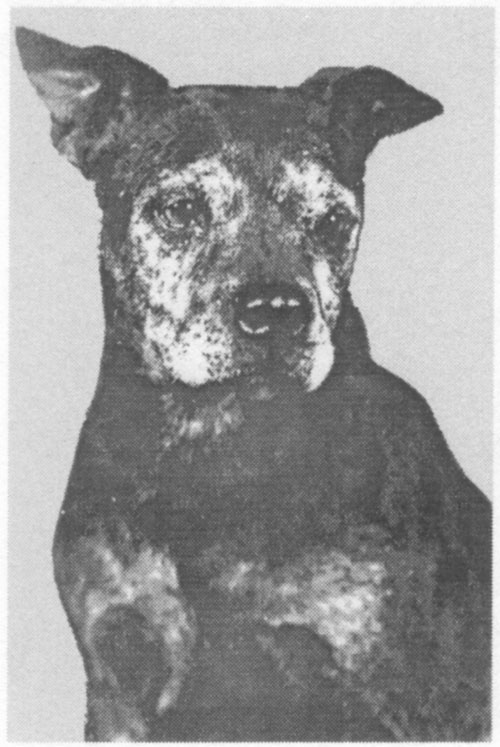

He had short black hair on his head and back, and fawn colored hair on his chest and belly (when it was clean). He walked on four bowed legs and had a whip-like stubby tail, which was almost completely devoid of hair. One ear was split and flopped over, while the other stood erect. He was about the size of a small boxer dog or bulldog. However, he must have had some chow dog somewhere in his lineage because he had a black tongue and mouth as seen in those breeds. All in all, he didn't present a handsome appearance no how charitable you tried to be in describing him. |

||

His age could be judged, at about five years, only by the battle scars, which covered his un-lovely husk. He looked, to some observers, as if he had walked into a turning aircraft propeller and survived. In fact, he had run under a revolving “G” ship prop and had two inches of his tail chopped off. Most dogs would have shunned airships from that moment forward, but not Blackdog. He considered himself cut to size, from then on, and continued to run under props whenever it suited him. |

||

A singular attribute of Blackdog was his complete independence. He certainly knew his way around, and he never failed to turn up at the proper place to be fed or to be taxied to the next destination. He was definitely partial to Navy enlisted men and indifferent to chief petty officers and civilians. He was almost openly contemptuous when an officer tried to befriend him. |

||

Details of Blackdog’s life at Fisher’s Island, and later at Airship Squadron Twelve at South Weymouth, Massachusetts, are obscure. It is known that he made several successful airship flights and became an expert airship ground handler. For those who don’t know what a ground handler might be, it is best explained that they were the men who tended the airship handling lines during takeoffs and landings. In many cases they used to literally pull a “light” airship right out of the sky. Blackdog was always the first to grab the “bitter end” of a line and the last to let go of it during airship operations in which he participated. To some of his shipmates this was a source of amusement – to others, a nuisance. However, Blackdog was always there, tugging on his portion of the line. In summer or winter, night or day, in rain or snow, if you were the end-man on an airship short-line, you could always feel the downward tug of a growling dog. |

||

| During take-offs, after the airship made headway down the mat, Blackdog would drop his end and run between the dragging short-lines as the ship took off over his back. The action was so routine that newly arrived sailors in the crew sometimes thought Blackdog was showing the pilots of the departing ship the upwind take-off path along the mat. Once, however, he was hit on the back by a ship’s wheel as the pilot endeavored to lift the big airship over the running dog before becoming completely airborne. It is believed that this was the beginning of a long list of visits to the veterinarian that Blackdog suffered during his long life. However, this particular incident did not stop Blackdog from running in the path of airships. He simply learned to swerve to one side as the ship approached him from the rear. | ||

After World War II Blackdog was taken to the Lakehurst Naval Air Station, New Jersey, along with the personnel of Airship Squadron Twelve and their fleet of “K” airships. ZP-12 took up residence there in Hangar Five, which was to be Blackdog’s home for six years. During that period, ZP-12 was de-commissioned and became Airship Squadron Two (ZP-2). It was then the exploits of Blackdog could most accurately be told. |

||

It was there that he encountered his first muskrat while he was patrolling one of the hangars with the security watch. He jumped a big one, but the rodent grabbed Blackdog by the throat and hung on. The sailor finally managed to kill the muskrat, but by that time Blackdog was in bad shape. He was taken to the hospital again. |

||

At Lakehurst, the Navy mess hall was approximately two miles from Hangar Five, thus necessitating the ZP-2 personnel to be transported to and from meals by bus or van in order to save time. It was during these trips that Blackdog would leave the hangar along with the men in order to receive a “hand out” from the cooks in the galley who never failed to keep him well fed. However, he seldom made the return trip in the van. He chose, instead, to visit his female friends belonging to the officers living nearby in base quarters. This often resulted in having to fight some high-ranking officer’s male dog on his way back to the hangar on foot. He seldom won these fights, especially since most of the dogs he fought were bigger than he and were fighting on home ground. But he always managed to survive with a few more scars to be added to the many already decorating his body. |

||

Blackdog was seldom absent from the hangar for any great length of time. He usually slept and on a coil of line or a pile of canvas blower sleeves under a tethered airship inside the hangar. He slept during the day, so he could patrol the hangar at night with the security watch, or the pressure watch whose duty it was to maintain a constant vigil over the airships. During these nights, he hunted rats, or any other unwelcome animal residing in his domain. For these reasons, Blackdog’s rabies shots were always kept up to date. For such routine visits to the veterinarian, and any emergencies that he might suffer, Blackdog had a special hospital fund, which was maintained by the leading Chief of the squadron, and was financed by the men. In that fund, there was always sufficient money so that their mascot could get good medical treatment when necessary. |

||

Blackdog never failed to delight the men while hunting a rat or mouse during those long night hours of patrol through the huge hangar. Sometimes he would get so excited in chasing these rodents that he would run on the hard concrete deck faster than his paws could get traction enough for a fast start. This resulted in his stubby legs running in place before forward motion could be achieved. Then when he finally did get up forward momentum, he would rocket into the hangar wall with a loud bang as his hard head made contact with the wall. Afterwards, he would sit at the hole for hours waiting for the rodent’s reappearance. |

||

Another sport he enjoyed was chasing a tin can over the hangar deck while pushing it with his nose, as it rattled and banged on the hard concrete floor, and barking at it incessantly. It often became necessary to remove the can in order to get some peace and quiet in the hangar. |

||

When the word was passed over the squadron public-address system for the duty section to muster on the quarter-deck, Blackdog always appeared with the men. Sometimes, the desk watch would call him by name to “lay down to the duty desk” for night rations (usually a ham sandwich). As usual, Blackdog would appear to receive his share of the evening snack offered to the night’s duty section. Sometimes an unscrupulous desk watch would try to fool him by calling his name at unscheduled times. This was only successful a few times before Blackdog learned when the call was in earnest or not, and he would govern himself accordingly. Blackdog was a familiar sight at squadron personnel inspections. He would stand in the ranks of the uniformed crew alongside the squadron-leading Chief, and often followed the Captain of the squadron through the ranks of the men while the inspection was carried out. It almost seemed as if he was personally passing judgment on the looks of the crew along with the inspecting officer. |

||

None of these personality quirks of Blackdog were encouraged by the men because they learned that nobody could teach him anything. He did as he pleased, and learned what he considered to be important to himself and disregarded everything else. He never became affectionately attached to any of his shipmates for any length of time, and generally showed complete indifference to those who went out of their way to be friendly with him. Yet, he was never mean nor did he ever bite anybody. |

||

He once demonstrated un-dog like intelligence by begging a sailor for walnuts, which the man carried in his lunch pail. Everybody knows that dogs don’t eat walnuts. However, the sailor finally gave in an offered the begging hound a handful of nuts which Blackdog proceeded to toss into the air and let them fall to the hard concrete floor where they cracked open. Then he could pick out the meats and eat them. |

||

For several years at Lakehurst, Blackdog faithfully manned (or dogged) his duty station in the ground handling crew. He was often seen running ahead of the ship in snow up to his belly. He was out on the mat when it was so cold that he would stand on three legs just to keep one of his feet in the air off the icy mat. The same principle applied in the summer when the mat was too hot for his thick paws. Someone once took pity on him and made the mistake of locking him in a room of the hangar during airship operations so he wouldn't go out on the boiling hot mat. He scratched and clawed his way right through the plaster-board wall and sped out to the area of a landing airship so he could take his place in the advance party with the other sailors. Nobody ever tried that again until he was much too old for such actions. |

||

In August 1951, ZP-2 received orders for a permanent change of duty station to NAS Glynco, Georgia. As the last ship crossed over the hangar sill to fly south, the radioman from the flight crew climbed out of the ship and grabbed Blackdog and put him aboard. Photographs were taken of this event, which still appear in ZP-2’s official history. When the ship was airborne, Blackdog went forward to the radio compartment and lay down under the navigator’s table, just as though he had done it many times before. Ten hours later when they landed at Glynco, Blackdog was still behaving himself under the table. When the ship was in the hands of the ground handling crew, Blackdog was handed down to the men in the car party at the foot of the ship’s ladder and turned loose. He immediately headed for the tall green grass surrounding the field and wasn't seen again until later that night when he showed up for supper at the mess hall with his shipmates, just as though he had lived there all his life. He settled into his new home with ease and carried on the same routine as he had experienced at Lakehurst. |

||

By this time Blackdog was getting along in years by dog standards. His actual age was 12 years, which amounts to 84 years compared to humans. He didn't appear much different except that he began to show gray around his mouth. However, he began to lose some of his teeth. Consequently, he often ended up second best in fights with other animals that he would start, but couldn't finish. As a result, his trips to the animal clinic increased in frequency in order for him to get patched up after being ripped by well-toothed dogs or raccoons. A well-meaning sailor once took Blackdog home with him to nearby St. Simons Island, Georgia, in order to let him rest at night on a warm rug, run on soft green grass and feast on good home cooked food. With Blackdog, that didn't last longer than one night. The sailor finally found him trying to cross the St. Simons Island causeway to the mainland. He was heading back to the only home he wanted – the ZP-2 hangar. No one ever tried to put him “out to pasture” again. |

||

One night the ground handling party was lined up on the Glynco mat to land an approaching airship. Out ahead of the forward advance party where the crew would eventually have to run to catch the airship lines, Blackdog set up a frantic barking and yelping in the pitch-black night. The ground-handling Chief ran out to see what the commotion was all about. When he directed his flashlight on the scene, there was Blackdog confronting a coiled-up, six-foot long water moccasin. It was all the Chief could do to call him off before he was bitten. The snake was killed, and there wasn't a man on that crew who wasn't extremely grateful to that mongrel dog being on the field that night. They knew one of them would have been bitten if it hadn't been for him. |

||

| In general, all these incidents are but a buildup to the most spectacular event in Blackdog’s life. Late at night during the hurricane season of 1953, the squadron received orders to deploy all of its airships away from Glynco out of the path of an approaching hurricane that was coming up the coast of Florida . One by one these ships took off and headed toward their respective deployment areas. In one of the ships, a pilot wondered why only one of the airship’s short lines was trailing back from the nose of the aircraft and showing in the forward running lights. The opposite line was missing from view. By directing the ship’s spotlight up to the nose of the ship, the missing line was discovered hanging straight down from the nose. The pilot followed the line down to its length to the end – and there was Blackdog, hanging head down by one leg, which was taken in a hitch by the short line. It wasn't possible to tell if he were alive or not because he wasn't moving his body at all. However, in case he was alive, a message was sent back to Glynco reporting the situation and requesting permission to return to base and try to save the beloved mascot. The ZP-2 Commanding Officer, after weighing the situation carefully, and considering the anxious men in the Squadron who loved the dog, allowed the ship to return to base long enough to drop Blackdog in the arms of five men in the rear of a stake-body truck traveling on the mat ahead of the airship, which was directed to make a low pass over the field. The whole maneuver was carried out flawlessly, and Blackdog, after flying an hour and seventeen minutes head down hanging from that airship line, was released from the line. The airship then continued on its mission and Blackdog, still alive, was taken to another one of his visits to the veterinary clinic to recover. His pads on all four feet were worn thin where he had scraped them on the mat during that harrowing take-off. At first he was unconscious and kept very quiet when he arrived at the clinic. However, he soon recovered and was kept very still for two weeks while the vet watched carefully over him. Miraculously, he suffered very little permanent damage. The muscles and tendons in one leg were severely bruised, but unbroken. Later he was returned to duty at Glynco. | ||

| His wounds were healed, but he was no longer the running, happy dog that the sailors had known before. His old body had endured the ultimate pain and suffering, and the decision was made to end his ground handling for the remainder of his life. Whenever airship operations took place on the mat from then on, a sailor was detailed to find Blackdog and take him to a secure room in the hangar where he would be compelled to stay until ground handling was completed. This action was taken with the very best of intentions toward Blackdog. It was in the nature of an honorable retirement for the old dog, but it just about broke his heart. He went through the motions of routine hangar life, but his friends could see that he no longer carried on with his old verve and love of life. For a dog that had lived his best, as he saw it, old age was just another enemy he could not lick. | ||

One morning in 1957 Blackdog was found on a coil of line under an airship, where he had died in his sleep. The men of ZP-2 felt the loss so much that they donated enough money to buy him a headstone to be placed over the small grave where he was laid to rest beside the entrance to the ZP-2 hangar. In his life, eighteen years, or one hundred and twenty-six dog years, he had been a constant companion and an inspiration to the men of lighter-than-air. Many still remember the barrel-chested mutt who was homely, ragged and usually dirty, and who would seldom reward you with a lick on the hand. But he was respected and admired by all. You couldn't pet him without getting grease on your hand, but he was never expelled from the presence of his shipmates with whom he lived, just for being dirty. He was a faithful companion to all, and though he lived a long life, it was by no means an easy one. |

||

| When ZP-2 was decommissioned in September 1959, the last squadron commanding officer decided that Blackdog’s headstone should be shipped to Lakehurst where the only remaining airship squadron (ZP-3) was based, in Hangar Five where Blackdog formerly lived. It was installed on the quarter-deck of that squadron. On November 18, 1959, Commander F. N. Kline of Fleet Airship Wing One rededicated Blackdog’s headstone in an unveiling ceremony before personnel of the last two airship squadrons. The memorial, with a perpetual light overhead, read as follows: | ||

| BLACKDOG |

||

| 1939-1957 |

||

A Good Shipmate |

||

A plaque was mounted on the wall behind the stone, reading – |

||

| “Though Blackdog’s remains are interred at Glynco , Georgia , his headstone is placed here on his old quarter-deck to perpetuate his memory in lighter-than-air.” | ||

Seldom has such recognition been given to a dog. But no one who knew him will ever deny he deserved it. |

||

Later when ZP-3 joined the rest of the airship Navy in de-commissioning, Blackdog’s memorial was transferred to the [promised] Lighter-Than-Air Museum in Hangar One in Lakehurst. Finally when all LTA activities ceased at Lakehurst, the memorial was sent to Flag Point in Toms River, New Jersey. This was the home of Vice Admiral Charles E. Rosendahl, USN (Ret), who was an early pioneer of airships and was considered to be the “father of all lighter-than-air” in the U.S. Navy. He promised to keep the memorial to Blackdog until he, himself, passed away. |

||